On 26 September 2023, I attended the official opening of the “Professor Ian Taylor Collection” at the Institute for Peace and Security Studies (IPSS) at Addis Ababa University.

After more than two years of team effort to fundraise and organise the transfer of the private library of the late Professor Ian Taylor, we were extremely grateful to see the beautiful new home of the book collection.

Here you can read the speech I delivered at the official opening ceremony at the IPSS:

Dear Director Dr. Fana Gebresenbet,

dear Mr. Ockenden,

dear Mr. Bekele,

dear IPSS team,

dear Jo,

dear friends and colleagues of Ian who join us from all over the world,

Today, we inaugurate the Professor Ian Taylor Collection here at the Institute for Peace and Security Studies at Addis Ababa University.

Ian Taylor passed away in February 2021 after a short struggle with cancer. He was Professor in International Relations and African Political Economy at the University of St Andrews in the UK. He also held extraordinary and visiting professorships at Renmin University and Zhejiang Normal University in China and at Stellenbosch University in South Africa. Ian was also a visiting professor at Addis Ababa University. For several years, he taught PhD students here at the IPSS, an institution which he spoke highly of and which he very much enjoyed visiting regularly.

As one of Ian’s former PhD students, I was asked to speak about Ian’s journey as a scholar today. This is everything but an easy task, considering the sheer volume and diversity of scholarship Ian had produced over the two and a half decades of his academic life. Ian wrote 12 academic books and co-edited another 14. He authored just under 100 peer-reviewed articles and countless chapters, reports and other publications.

Ian was co-editor-in-chief of Cambridge University Press’s prestigious Journal of Modern African Studies and a co-editor of African Security. He had established himself as a world-renowned scholar in the fields of African Studies, China-Africa Studies, International Relations and Global Political Economy.

Shaun Breslin of the University of Warwick, one of Ian’s close companions, put it pointedly in a televised address at a thanksgiving service for Ian’s life in St Andrews in 2021. He said – and I quote:

‘I don’t think I’ve ever met anybody who knew so much about so many places and issues. And he didn’t just know about them – he published on them too. What this means is that if you asked five people to say what they thought of Ian’s work and asked them to sum up his contribution, they could easily focus on five different dimensions of it; indeed, you might end up thinking that they were talking about different people or that there were multiple Ian Taylors out there.’

Shaun Breslin is right. In my own conversations with Ian – and I am sure many of you experienced the same, I regularly encountered different Ian Taylors. The most remarkable aspect of his intellectual personality was that the multiple Ian Taylors spoke to one another in a coherent and intellectually stimulating manner. Thereby, Ian never thought in disciplinary categories and boundaries. He was actually a post-disciplinary scholar long before this became fashionable.

As Shaun Breslin pointed out, it was simply impressive with how many thematic and disciplinary discourses Ian kept up, and how diverse his research and body of work is. Ian was a polymath. The personal library of about 7,000 books that we inaugurate today is proof of how widely Ian read and how knowledgeable he was. In the shelves surrounding us you’ll find books on pretty much all African countries, on political economy, political science, sociology, International Relations, Marxism, China, and many other topics.

So, in the next few minutes I won’t be able to do justice to the many Ian Taylors out there. I will much rather sketch some of the personal and professional milestones in Ian’s life to honour a truly outstanding intellectual as well as a passionate educator. After sketching Ian’s own journey, I will briefly talk about the journey of his personal library which has found a new and beautiful home here at the IPSS.

Ian’s Taylor’s journey

Ian’s journey started on the Isle of Man where he grew up with his twin brother Eric. Eric would have wished to be here today, but is currently serving at the British Embassy in Sierra Leone. Incidentally, Eric was posted to Ethiopia for six months in 2017 and met his brother here during one of Ian’s academic trips to Addis. Eric joins us via Zoom today.

The twins and their family later relocated from the Isle of Man to West London, where Ian spent his teens and would become a die-hard Brentford FC supporter. He would have certainly rejoiced to see his team fretting the big Premier League clubs since 2021.

While there were few points of contact with Africa on the Isle of Man, Ian, early on, developed a keen interest in Africa, as he heard stories from his grandmother, whose parents had lived in South Africa, where a large network of relatives still lives.

Ian first read History and Politics at what was then the Leicester Polytechnic. Supervised by Gurharpal Singh, Ian concluded his Bachelor’s with a thesis on Albania, which was inspired by a trip he had undertaken in 1986 when he was only 17. Following his undergraduate studies, Ian used a gap year in 1991/92 for his first travel to southern Africa – obviously at quite a formative time for the region. This trip clearly left a firm impression on him, as he would continuously return to the region throughout his life.

First, however, Ian joined Joanne whom he met in South Africa. Jo took up PhD studies at the University of Hong Kong in 1994 and Ian enrolled himself for a Master’s there. His 368-page MPhil thesis on China’s foreign policy vis-à-vis Africa, which was supervised by James Tang, laid the cornerstone for one of his research specialisations and arguably also for a new sub-discipline, China–Africa studies. One publication outcome of this thesis was an article titled “China’s foreign policy towards Africa in the 1990s” which was published in the Journal of Modern African Studies (Taylor, 1998), the very journal whose co-editor-in-chief Ian would later become, together with Ebenezer Obadare. Today, this article is cited 382 times.

In 1996, Ian moved to South Africa – Jo followed several months later. At Stellenbosch University, Ian pursued his PhD studies under the supervision of Prof. Philip Nel. With his PhD research, Ian delved deeply into South African foreign policy and into the neoliberalisation of the post-apartheid African National Congress and, by extension, the South African state (Taylor, 2001).

In a forthcoming special issue on the life and work of Ian Taylor which I co-edited with Gillian Brunton and Faye Donnelly who are with us on Zoom I think, Ian’s PhD supervisor Philip Nel details the intellectual development of the “early” Ian Taylor. Nel elaborates that, at the time, Stellenbosch’s Political Science department gathered a group of scholars who had become rather disillusioned about remaining inequities in the post-Cold War global order. They were inspired by the work of critical political economists like Susan Strange, Robert Cox, Stephen Gill and William Robinson, as well as by critical Africanists such as Timothy Shaw, Patrick McGowan and Craig Murphy.

It was within this particular intellectual environment that Ian developed – and I quote Philip Nel – a ‘distinctive Coxian and Gramscian theoretical approach’, which ‘allowed him to link the dynamics of ideational factors with the material interests of actors – an ideology critique in the original sense of the phrase’.

Ian’s work rapidly spiralled beyond his PhD research on South African foreign policy. I know of few scholars with a similar research output so early in their career. As Janis van der Westhuizen from Stellenbosch University expressed humorously in an email conversation and I quote: ‘when we shared an office as PhD students, he would churn out one article for every two pages I was able to write!’.

Rapidly, Ian became an important representative of the Stellenbosch School of critical global political economy (Vale, 2002). As Professor Extraordinary, he would return to his alma mater throughout his life and continue to inspire generations of students there.

Tit-for-tat, after finishing his PhD, it was again Ian’s turn to “follow” his wife. The two moved on to the University of Botswana, where Jo had been offered a teaching position and where their first child, Blythe, was born in 2004. Their second-born Archie would follow two years later in Scotland.

Ian took up a lectureship in Gaborone and was soon promoted to senior lecturer. Among his students was Kennedy Kamoli, who would, in 2014, stage a coup d’état in Lesotho – an occurrence that Ian, with his typical humour, often referred to as his only “claim to fame”. It was during his time in Gaborone that Ian, together with his close friend Fredrik Söderbaum, launched a “second wave” of critical research on African regionalisms in the tradition of the New Regionalism Approach (see Taylor 2003a; Taylor and Söderbaum 2003). Concurrently, Ian published a rigorous critique of the neoliberal underpinnings of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) (see Taylor, 2005). In the same time period, he also authored influential articles on other African affairs, for instance one, together with Paul Williams, in International Affairs on British foreign policy and the Zimbabwe crisis and several articles on conflict dynamics in Central Africa (see Taylor and Williams 2002; Taylor 2003b).

In 2004, Ian was appointed to a faculty position in the School of International Relations at St Andrews where he, thanks to his enormous productivity, quickly climbed the tenure track to full professorship. Shortly before his death, Ian was awarded a Doctor of Letters by the University of St Andrews for his life’s work.

Ian was not only a prolific, highly respected scholar and passionate educator. I have been told by many of his colleagues from several institutions at which Ian worked that he was also a great colleague and co-worker. Indeed, his enthusiasm for institutional “house-keeping”, as well as for the usual admin and politics that come with a university job, had definite limits. Yet, his colleagues commonly remember how genuinely interested and supportive he was of their work, sharing generously with them his contacts, knowledge and advice. Even more importantly, Ian never differentiated according to the “rank” of the people with whom he engaged. He treated everyone respectfully (usually combined with a good amount of humour) regardless of one’s societal or professional role. He would remember the birthdays of co-workers and would happily join the Christmas functions of the administrative staff at the School of International Relations.

Once established as a leading scholar in his field, Ian published an immense body of works which includes, among others, monographs on China–Africa relations (Taylor, 2006; 2009; 2011), on the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Taylor and Smith, 2007) and on the international relations of Africa (Taylor, 2010). He also authored Oxford’s Very Short Introduction to African politics(Taylor, 2018). Incidentally, Jo and myself inquired in a book shop in the city centre of Addis Ababa a few days ago about Ian’s book on African politics, since the shop stored all of the other titles of the Oxford series A Very Short Introduction. The answer from the staff at the shop was that his book was “finished” – in other words: sold out.

Ian also offered a much-needed discursive corrective to the overenthusiastic narrative about the transformative impact of so-called emerging powers in global governance (Taylor, 2017) and he famously argued that the BRICS countries were diversifying Africa’s dependency instead of diminishing it (Taylor, 2014a). I am convinced, that his work on the BRICS will reverberate in the context of the BRICS grouping’s recent enlargement.

Numerous critical interventions in article form, such as the ones on state capitalism and Africa’s oil sector (Taylor, 2014b), the (neo-)coloniality of the Communauté Financière Africaine (Taylor, 2019) and on China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Africa (Carmody, Taylor and Zajontz, 2022), have attracted much attention in scholarly circles and beyond. Ian had become ‘one of the most authoritative academics’ on sub-Saharan Africa’s international relations, as he was once called in the Cambridge Review of International Affairs (Anesi, 2012, p. 171).

Besides his remarkable academic achievements, Ian was an extremely passionate educator, as well as a kind, humorous and supportive colleague and friend to many people around the world. Ian’s untimely death caused much grief, not least among his colleagues and students at the institutions he worked at.

Throughout his career, Ian remained steadfast and loyal to his political ideals of a more equitable and just world. He was a radical, a very gentle radical. He never compromised on his convictions of what is right and what is wrong. What he most certainly considered wrong was the enduring systematic exploitation of Africa by external actors and economic interests. At the same time, he would never let African political and economic elites escape from their responsibility for the fate of their people. His neo-Gramscian training and his appreciation of the complexity of state-society relations, as well as his familiarity with the political thought of theorists like Claude Ake, Samir Amin, W.E.B. Du Bois, Amílcar Cabral, Frantz Fanon, Kwame Nkrumah, Walter Rodney and others, prevented him from making reductionist and Eurocentric assumptions about Africa’s role in the international system and global political economy.

Ian was an extremely hard-working academic, who was marked by his humility and pride in his working-class background. In contrast to some other leading scholars, he really listened when others spoke. Ian incorporated silenced voices, not least from the African continent, into his work and actively engaged in diversifying thought at the institutions he taught by embracing previously unheard or ignored ideas.

Throughout his life, he remained a keen “student of Africa”. He visited 44 African countries. Whenever he found himself guest lecturing at Addis Ababa University, he would check Ethiopian Airlines’ vast route network and book a flight to one of the few African destinations he had not been to. Wanderlust and curiosity were innate to Ian. His untimely death prevented him from completing his personal “Africa journey”. Yet, he fully accepted his fate and was immensely grateful for the help he received from medical staff, as well as for the love of family and friends. It was obvious that his firm belief in God gave him faith, no matter what might be.

The journey of Ian Taylor’s books

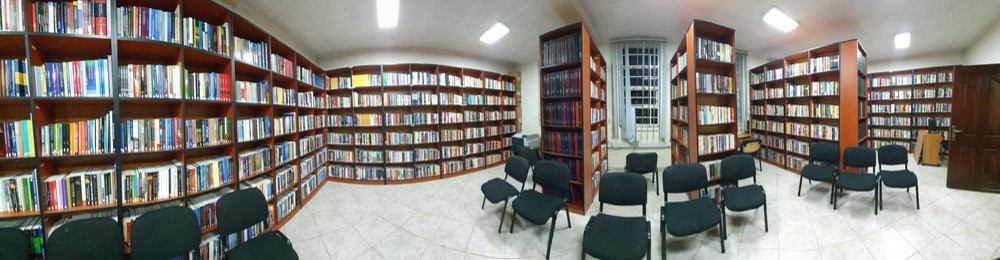

Having outlined some of the milestones in Ian’s life, I would like to still share with you how his personal library has ended up here at the IPSS. Last Wednesday when I walked into this room for the first time, it did not take long until I was overwhelmed by strong emotions. The books brought back fond memories of a person who we all miss dearly. I remembered sitting in Ian’s St Andrews office surrounded by these books chatting to this incredibly knowledgeable man.

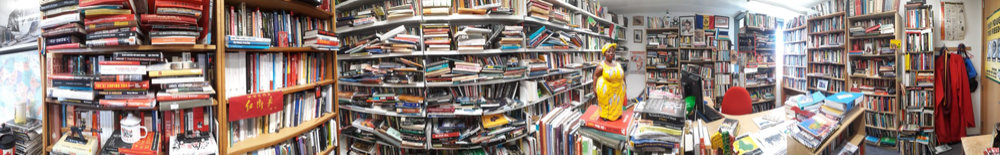

You must imagine that Ian’s office had probably a third of the size of this room. He not only had shelves along all walls. No, he also had shorter ones around his desk. As Jo noted, the shelves were stuffed with books as well as with souvenirs from all over the world.

Ian’s office was legendary, among both students and faculty in St Andrews. It was kind of a sight in the building of the School of International Relations. Undergraduate students would regularly stop by his office to catch a glimpse of what was certainly the room with the highest book per square metre density in St Andrews. Ian’s office door stood most of the time open. He literally had an open-door policy towards his students and was very approachable for them.

Yet, I got emotional last week not only because I remembered a very special person. I also remembered the process of how these books were moved from this little town in the East of Scotland to Addis Ababa. It was about a week after Ian’s death that Jo had visited me in my home in St Andrews. Our conversation also came to the topic of what we should do with all these books. For Jo one thing seemed crystal clear: There was certainly no scenario in which this immense amount of books would enter their home in St Monans. Not least because Ian had accumulated another 2,000-3,000 books at home.

A few weeks later we conspired again. Ian’s twin brother Eric joined us. All three of us knew that Ian would want these books to be accessible to students and scholars in Africa, the continent he had dedicated his academic career to. It was also clear to us that the impact of such an amazing collection would be probably greatest at the IPSS where Ian had worked as a visiting professor for several years. We also remembered that Ian had always reported how much he had enjoyed his stays at IPSS and the company of the IPSS staff and students. So, the mission was defined: we planned to move about 7,000 books from St Andrews, Scotland, to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Remember, this was in mid-2021 at the peak of the Corona pandemic. So, let the mission begin…

We started liaising with the IPSS. The first contact was made with the help of Prof. Ulf Engel from the University of Leipzig. Ulf linked us to then IPSS Director Dr. Yonas Adeto and to Dr. Frank Owusu. We were pleased to learn from them that the IPSS was happy to receive the books. So, we entered the second stage of the mission in late 2021 – let me call this stage: the logistical stage.

I remember Whatsapp phone conversations with you, Munib, about your library software system, video calls about the size of the room and the measurements of its doors. Frank, you and I discussed the possibility to install a library security system, the one you see at the entrance now, which of course meant that each and every book would need a security tag, a task which was later taken on by Ms. Muratsi. I remember photos taken by you Mr. Zewdie of the entrance door in order for the British company to fit the security equipment. I recall endless email threads with you, Dr. Fana and Mrs. Seble, in which we cleared bureaucratic hurdles for the transfer to proceed.

I not least remember our crowdfunding campaign. Jo, you and I were sometimes messaging one another screenshots of the status of the balance of donations, moved by the generosity of friends and even of strangers who supported our rather crazy idea.

The other day, Jo and I were guesstimating that, all communications included, we probably exchanged about 2,000 emails and letters and had about 50 meetings in the preparation of the library transfer. This was among ourselves, with people from the University of St Andrews, with IPSS, with the Ethiopian Embassy in London, with the British Embassy in Ethiopia, with shipping agents, with shipping firms, with donating organisations, with various individuals.

When I entered the library last week, I was touched by our joint accomplishment. I want to thank you Dr. Fana, you Mrs. Seble, Dr. Frank, Mr. Munib, Mr. Meheret, Mr. Zewdie, Ms. Muratsi and all of you from IPSS for the immense effort you have put into this. We are so happy and grateful that you saw value in this mission.

I also want to thank the Ethiopian Embassy in London, notably H.E. Ambassador Teferi Melesse and the Deputy Head of Mission, Beyene Meskel, who I believe is with us today on Zoom. Many thanks for supporting our idea. A huge “thank you” also to the British Embassy here in Addis Ababa which supported the transfer of the books with a generous donation. Thanks are also due to the Germany-based NGO Freundeskreis Uganda for their generous donation. Special thanks for the generosity of Ian’s family on the Isle of Man. Lastly, I want to thank the many individuals who supported the establishment of the Ian Taylor Collection at the IPSS through their donations. Without you, this would not have happened.

I want to pass a congratulatory message to you which we recently received from Professor Dame Sally Mapstone, Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of St Andrews, where Ian had worked for almost twenty years. Professor Dame Mapstone wrote – and I quote:

The donation of over 7000 books to the IPSS will improve the teaching and research of innumerable staff and students at the University of Addis Ababa for generations to come, and there could not be a more fitting testament to Ian’s memory as a much loved and much respected teacher.

As someone who has himself profited a lot from the treasure that this collection of books is, I am very happy and very grateful about this successful team effort. It is so good to know that Ian’s personal library is looked after by such an amazing team and can be used by students and researchers here at the IPSS. Thank you to everyone who was involved in making this possible. Ian’s intellectual life has now an additional home: the Institute for Peace and Security Studies at Addis Ababa University.

Thank you very much.

Before: Ian Taylor’s books in his office at the University of St Andrews

After: The “Professor Ian Taylor Collection” at the Institute for Peace and Security Studies

References

Anesi, F. 2012. ‘Book reviews’, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 25(1): 171-190.

Carmody, P., Taylor, I. and Zajontz, T. 2022. ‘China’s spatial fix and ‘debt diplomacy’ in Africa: constraining belt or road to economic transformation?’, Canadian Journal of African Studies, 56(1): 57-77.

Söderbaum, F. and Taylor, I. (eds.) 2003. Regionalism and Uneven Development in Southern Africa. London: Routledge.

Taylor, I. 1998. ‘China’s Foreign Policy towards Africa in the 1990s’, The Journal of Modern African Studies, 36(3): 443-460.

Taylor, I. 2001. Stuck in Middle GEAR: South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Relations. Westport: Praeger.

Taylor, I. 2002. ‘The New Partnership for Africa’s Development and the Zimbabwe Elections: Implications and Prospects for the Future’, African Affairs, 101(404): 403-412.

Taylor, I. 2003a. ‘Globalization and regionalization in Africa: reactions to attempts at neo-liberal regionalism’, Review of International Political Economy, 10(2): 310-330.

Taylor, I. 2003b. ‘Conflict in Central Africa: Clandestine Networks and Regional/Global Configurations’, Review of African Political Economy, 30(95): 45-55.

Taylor, I. 2005. NEPAD: Towards Africa’s Development or Another False Start? Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Taylor, I. 2006. China and Africa: Engagement and Compromise. London: Routledge.

Taylor, I. 2007. ‘What Fit for the Liberal Peace in Africa?’, Global Society, 21(4): 553-566.

Taylor, I. 2009. China’s New Role in Africa. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Taylor, I. 2010. The International Relations of Sub-Saharan Africa. New York: Continuum.

Taylor, I. 2011. The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). London: Routledge.

Taylor, I. 2014a. Africa Rising? BRICS – Diversifying Dependency. Oxford: James Currey.

Taylor, I. 2014b. ‘Emerging powers, state capitalism and the oil sector in Africa’, Review of African Political Economy, 41(141): 341-357.

Taylor, I. 2014c. ‘Is Africa Rising?’, The Brown Journal of World Affairs, 21(1): 143-162.

Taylor, I. 2017a. Global Governance and Transnationalising Capitalist Hegemony: The Myth of the “Emerging Powers”. London: Routledge.

Taylor, I. 2017b. ‘The Liberal Peace Security Regimen: A Gramscian Critique of its Application in Africa’, Africa Development, 42(3): 25-44.

Taylor, I. 2018. African Politics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, I. 2019. ‘France à fric: the CFA zone in Africa and neocolonialism’, Third World Quarterly, 40(6): 1064-1088.

Taylor, I. and Smith, K. 2007. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. London: Routledge.

Taylor, I. and Williams, P. 2002. ‘The Limits of Engagement: British Foreign Policy and the Crisis in Zimbabwe’, International Affairs, 78(3): 547-565.

Vale, P. 2002. ‘The movement, modernity and new International Relations writing in South Africa’, International Affairs 78(3): 585-593.