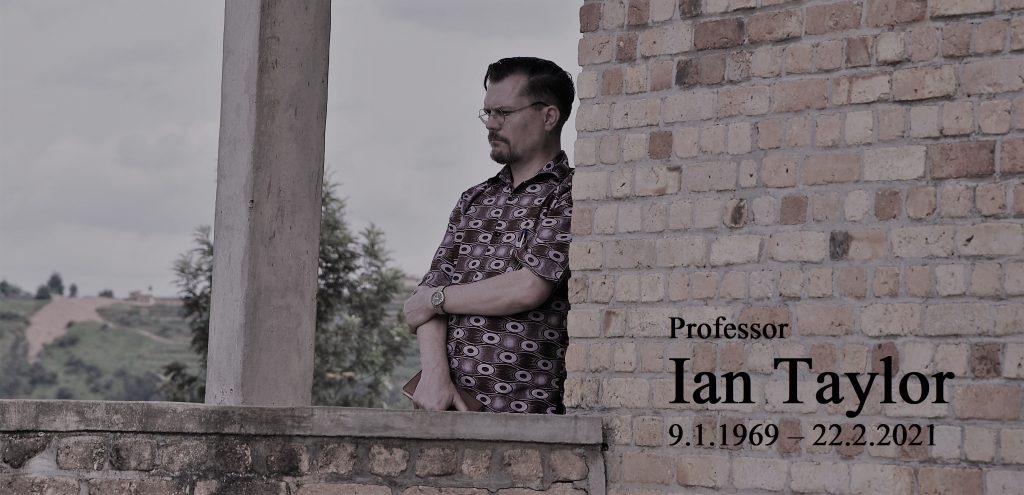

Last year in February, Professor Ian Taylor of the University of St Andrews passed away after a short struggle with cancer. Ian was a world-renowned scholar in the fields of African Studies, International Relations and Global Political Economy. Besides his remarkable academic achievements, Ian was an extremely passionate educator as well as a kind, humorous and supportive colleague and friend to many of us. This is a modest attempt at paying tribute to an inspiring intellectual and true friend of Africa.

Together with his twin brother Eric, Ian grew up on the Isle of Man, before the family relocated to West London where he spent his teens and would become a die-hard Brentford FC supporter – in his words a ‘100% local club’. Whilst there were few points of contact to Africa on the small Crown dependency in the Irish Sea, Ian, early on, developed an interest in Africa, as he heard stories from his grandmother whose parents had lived in South Africa, and where a large network of relatives still live.

After reading History and Politics at what was then the Leicester Polytechnic, Ian used a gap year in 1991-92 for his first travel to southern Africa – obviously at quite a formative time for the region. This trip clearly left a firm impression on him, as he would return to the region throughout his life. However, first he joined Jo, the love of his life whom he met in South Africa, when she took up Ph.D studies at the University of Hong Kong in 1994. Ian enrolled himself for a Master’s there. His 368-pages M.Phil thesis on China’s foreign policy vis-à-vis Africa laid the cornerstone for one of his research specialisations and arguably also for a new sub-discipline, China-Africa studies. One of his first academic articles, an output from his M.Phil research, was published in the Journal of Modern African Studies and has since been cited 357 times (Taylor 1998). Exactly 18 years later, Ian became co-editor-in-chief of this prestigious journal, together with Ebenezer Obadare.

In 1996, Ian moved to South Africa (Jo followed several months later) to pursue Ph.D studies at Stellenbosch under the supervision of Philip Nel. With his Ph.D research, Ian delved deeply into South African foreign policy and into the gradual neoliberalisation of the post-apartheid African National Congress and, by extension, the South African state (Taylor 2001). At the time, Stellenbosch’s political science department gathered a group of scholars who had become rather disillusioned about remaining inequities in the post-Cold War global order, and who were inspired by the work of critical political economists like Susan Strange, Robert Cox, Stephen Gill and William Robinson as well as by critical Africanists such as Timothy Shaw, Patrick McGowan and Craig Murphy (Nel forthcoming). As his Ph.D supervisor reflects, it was within this intellectual habitat that Ian developed a “distinctive Coxian and Gramscian theoretical approach” which “allowed him to link the dynamics of ideational factors with the material interests of actors – an ideology critique in the original sense of the phrase” (Nel forthcoming). Ian became an eminent voice of the Stellenbosch School of critical global political economy (Vale 2002). As Professor Extraordinary, he would regularly return to his alma mater and continue to inspire generations of students there and at other (African) institutions.

Tit-for-tat – after finishing his Ph.D, it was again Ian’s turn to ‘follow’ his wife. The two moved on to the University of Botswana where Jo had been offered a teaching position and where their first child, Blythe, was born in 2004. Ian took up a lectureship in Gaborone and was soon promoted to senior lecturer. Amongst his students was Kennedy Kamoli, who would, in 2014, stage a coup d’état in Lesotho – an occurrence that Ian, with his typical humour, often referred to as his only ‘claim to fame’. It was during his time in Gaborone that Ian, together with his close friend Fredrik Söderbaum, launched a ‘second wave’ of critical research on African regionalisms in the tradition of the New Regionalism Approach (see Taylor 2003a; Söderbaum and Taylor 2003). Concurrently, Ian published a rigorous critique of the neoliberal underpinnings of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) (see Taylor 2002, 2005) as well as several influential contributions on Africa’s international relations and conflict dynamics (see, for instance, Taylor and Williams 2002; Taylor 2003b).

In 2004, Ian was appointed to a faculty position in the School of International Relations at St Andrews where he worked as a Professor of International Relations and African Political Economy until his untimely death. Amongst both students and faculty in St Andrews, Ian’s office was legendary for the colourful book walls he had erected around his desk. No doubt, his office hosted the biggest private Africana library in Scotland. But there were also thousands of books on China, political economy, history, political thought, etc. Ian was a polymath. He was post-disciplinary (before it became fashionable) and eclectic (though not arbitrary) in the selection of theories and sources that he used to explain and critique developments on the continent and beyond.

Once established, Ian published an immense body of works which includes, amongst others, monographs on China-Africa relations (Taylor 2006, 2009, 2011), the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Taylor and Smith 2007) and on the International Relations of Africa (Taylor 2010), as well as Oxford’s Very Short Introduction to African Politics (Taylor 2018). He offered a much-needed discursive corrective to the overenthusiastic narrative about the transformative impact of so-called emerging powers in global governance (Taylor 2017) and famously argued that the BRICS countries were diversifying Africa’s dependency instead of diminishing it (Taylor 2014a, see also 2016). Numerous critical interventions in article form, such as the ones on state capitalism and Africa’s oil sector (Taylor 2014b), the (neo-)coloniality of the Communauté Financière Africaine (Taylor 2019) and China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Africa (Carmody, Taylor and Zajontz 2022), have attracted much attention in scholarly circles and beyond. Ian had become ‘one of the most authoritative academics’ on Sub-Saharan Africa’s International Relations, as he was once called in the Cambridge Review of International Affairs (Anesi 2012: 171).

Throughout his career, Ian remained steadfast and loyal to his political ideals of a more equitable and just world. He was a radical – a very gentle radical. He never compromised on his convictions of what is right and what is wrong. What he most certainly considered wrong was the enduring systematic exploitation of Africa by external actors and economic interests. At the same time, he would never let African political and economic elites escape from their responsibility for the fate of their people. Not only his neo-Gramscian training and his appreciation of the complexity of state-society relations but also his familiarity with the political thought of thinkers like Claude Ake, Samir Amin, W.E.B. Du Bois, Amílcar Cabral, Frantz Fanon, Kwame Nkrumah, David Rodney and others prevented him from reductionist or Eurocentric assumptions about Africa’s role in the international system and global political economy.

Ian was an extremely hard-working academic who was marked by his humility and proud of his working-class background. In contrast to some other leading scholars, he really listened when others spoke. He incorporated silenced voices, not least from Africa, into his work and actively engaged in diversifying thought at the institutions he taught at by embracing previously unheard or ignored ideas. Throughout his life, he remained a keen “student of Africa”. He visited 44 African countries. Whenever he found himself guest lecturing at Addis Ababa University, he would check Ethiopian Airlines’ vast route network and book a flight to one of the few African destinations he had not been to. Wanderlust and curiosity were innate to Ian. His untimely death hindered him from completing his personal “Africa journey”. Yet, he fully accepted his fate and was immensely grateful for the help he received from medical staff and for the love from family and friends. It was obvious that his firm belief in God gave him faith no matter what would come. May his soul rest in peace.

Dr Tim Zajontz is a Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Freiburg, Germany and a Research Fellow at the Centre for International and Comparative Politics at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. He tweets at @TZajontz.

“Ian Taylor Collection” in Addis Ababa

Ian’s family and friends are currently organising the transfer of Ian’s personal library (of about 8,000 books) to the Institute for Peace and Security Studies (IPSS) at the Addis Ababa University where Ian was a visiting professor. Please consider supporting this initiative by donating HERE.

References:

Anesi, F. 2012. ‘Book reviews’, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 25(1): 171-190.

Carmody, P., Taylor, I. and Zajontz, T. 2022. ‘China’s spatial fix and ‘debt diplomacy’ in Africa: constraining belt or road to economic transformation?’, Canadian Journal of African Studies, 56(1): 57-77.

Nel, P. forthcoming. ‘After Ian Taylor’, Contemporary Voices: The St Andrews Journal of International Relations.

Söderbaum, F. and Taylor, I. (eds.) 2003. Regionalism and Uneven Development in Southern Africa. London: Routledge.

Taylor, I. 1998. ‘China’s Foreign Policy towards Africa in the 1990s’, Journal of Modern African Studies, 36(3): 443-460.

Taylor, I. 2001. Stuck in Middle GEAR: South Africa’s Post-Apartheid Foreign Relations. Westport: Praeger.

Taylor, I. 2002. ‘The New Partnership for Africa’s Development and the Zimbabwe Elections: Implications and Prospects for the Future’, African Affairs, 101(404): 403-412.

Taylor, I. 2003a. ‘Globalization and regionalization in Africa: reactions to attempts at neo-liberal regionalism’, Review of International Political Economy, 10(2): 310-330.

Taylor, I. 2003b. ‘Conflict in Central Africa: Clandestine Networks and Regional/Global Configurations’, Review of African Political Economy, 30(95): 45-55.

Taylor, I. 2005. NEPAD: Towards Africa’s Development or Another False Start? Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Taylor, I. 2006. China and Africa: Engagement and Compromise. London: Routledge.

Taylor, I. 2009. China’s New Role in Africa. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Taylor, I. 2010. The International Relations of Sub-Saharan Africa. New York: Continuum.

Taylor, I. 2011. The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). London: Routledge.

Taylor, I. 2014a. Africa Rising? BRICS – Diversifying Dependency. Oxford: James Currey.

Taylor, I. 2014b. ‘Emerging powers, state capitalism and the oil sector in Africa’, Review of African Political Economy 41(141): 341-357.

Taylor, I. 2016. ‘Dependency redux: why Africa is not rising’, Review of African Political Economy Volume 43(147): 8-25.

Taylor, I. 2017. Global Governance and Transnationalising Capitalist Hegemony: The Myth of the “Emerging Powers”. London: Routledge.

Taylor, I. 2018. African Politics: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, I. 2019. ‘France à fric: the CFA zone in Africa and neocolonialism’, Third World Quarterly, 40(6): 1064-1088.

Taylor, I. and Smith, K. 2007. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. London: Routledge.

Taylor, I. and Williams, P. 2002. ‘The Limits of Engagement: British Foreign Policy and the Crisis in Zimbabwe’, International Affairs, 78(3): 547-565.

Vale, P. 2002. ‘The movement, modernity and new International Relations writing in South Africa’, International Affairs 78(3): 585-593.